This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

New regulation of platform work in Chile fails to tackle power imbalances between platforms and workers

The Chilean Congress will soon approve one of the first laws in the world to regulate platform work. This law will provide an answer to the question of how to classify and regulate a new type of work that has so far evaded existing labour regulations. Researchers from the Fairwork Chile team have released a policy brief analyzing the content of the law and how it may affect the thousands of platform workers in the country.

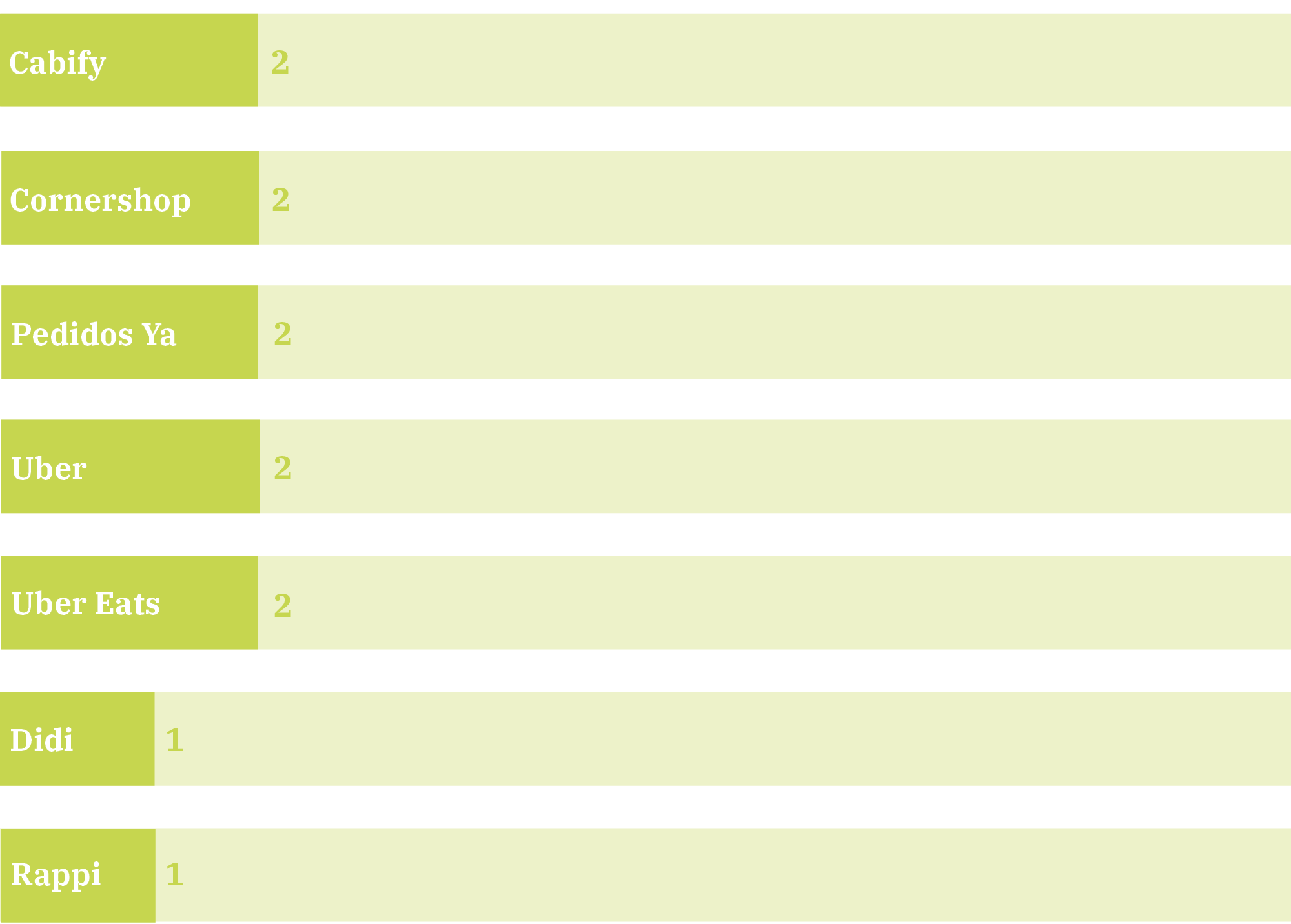

Behind these platforms’ promise of flexibility and autonomy, the reality is that platform workers often face long working hours, low and insecure pay, and dangerous working conditions. The Fairwork Chile Ratings 2021 make this evident: of the seven platforms analyzed, none scored more than 2 out of 10 points, meaning they failed to meet most standards of decent work. These problems can be boiled down to the disparities of power between platforms and their workforce, often of migrant and low-income background. Rather than alleviating these disparities, the platform economy has enabled even more intrusive forms of control and coercion in the workplace. The question now is whether this new law will be successful in improving the conditions in the sector and reverting existing power imbalances.

Fairwork Chile Ratings 2021 (out of 10)

Different rights for dependent and independent workers

One key feature of the new legislation is that it distinguishes between two types of workers: dependent digital platform workers and independent digital platform workers. The distinction depends on whether a subordinate and dependent relationship between the platform and the worker exists. The text assigns specific rights to each category, and some general protections applicable to both.

For dependent platform workers, the new law grants the same rights available to other employed workers, but with some special considerations. One of them is an adapted definition of working time that starts from the moment the worker “connects to the digital infrastructure and until he or she voluntarily disconnects”. The law also contemplates the option for workers to freely distribute their working time, as well as the possibility of choosing a remuneration system per unit of time or percentage of the tariff charged to users.

In contrast, independent platform workers are provided with a “light version” of the protections granted to dependent workers. Interestingly, some of the protections granted to independent workers are partially similar to those offered to dependent workers, such as the right to disconnect (for a minimum of 12 hours), an obligation of prior notice for contract termination (of 30 days), and norms relating to the protection of workers’ fundamental rights. However, these are only available to those who, in the last 3 months, worked for the platform for at least 30 hours on average each week.

Finally, the law sets some general rules for all platform workers:

- The obligation for the company to inform about the details of the services offered, such as the identity of the user or the location of the job.

- Rules on transparency and the right to information, including protection of workers’ personal data and of data portability rights.

- Anti-discrimination rules for automated decision-making mechanisms.

- Rules on training and personal protection elements to be provided by the platform

- Rules on the calculation of severance pay, taking as a basis the average remuneration of the last year worked.

- Rules on collective rights, including the right to form trade unions.

A missed opportunity?

Undoubtedly, the proposed law includes welcomed protections in terms of working hours, remuneration, personal data protection and anti-discrimination, which could significantly improve the conditions of workers in the platform economy.

However, the draft suffers from structural problems that could weaken its effectiveness in protecting platform workers’ rights. The main problem lies in the creation of two categories of workers, with independent providers only receiving a watered-down version of the protections offered to dependent workers. This distinction was created to allow for those who may want to keep the flexibility of their self-employed status. However, flexibility is not necessarily incompatible with an employment relationship. Furthermore, it is not clear that platform workers will get to decide their status. Considering the inequalities of power, it is not difficult to imagine that, faced with the possibility of choosing between a regime with more labour protections and one with less, companies would opt for the latter without giving the worker a choice. This likely means workers without protections will have to take platforms to court to prove their status as dependent workers.

The law also falls short in terms of collective representation rights. The new law will allow platform workers, even independent ones, to form unions and engage in collective bargaining. However, they will only be able to negotiate under the figure of so-called “unregulated collective bargaining”. In simple terms, this means bargaining without labour law protection and without the possibility of engaging in strike actions. These elements are two of the most relevant protections of collective labour law, allowing workers to articulate freely and without fear of reprisals from their employer. By removing them, the law fails to provide workers with adequate tools to defend their rights.

Overall, the proposed regulation presents some improvements to platform workers’ rights in Chile. But ultimately, this law is a missed opportunity to tackle the root of the problem: the power imbalances between platforms and workers. This would require a deeper reflection on the future of labour regulation, rather than a simplistic analysis of the economic benefits of platform work.