Bangladesh needs a policy framework for a growing platform economy

Shamarukh Alam, Researcher, Fairwork Bangladesh Ratings 2023; Senior Research Fellow, DataSense at iSocial

Not even a decade has passed since the introduction of gig platforms in Bangladesh; however, the country has seen significant growth of the platform economy. While ride-hailing and delivery work is often assumed by men, women are more likely to utilise platforms that provide domestic work, beauty services and care work.

According to the 2016-2017 Labour Force Survey, 85.1% of Bangladesh’s workforce is part of the informal economy. Contribution of the informal sector to the GDP is around 64%1a portion of which is quickly being claimed by the gig economy.

The country has seen a rapid expansion of both global and home-grown digital platforms, such as Uber, Pathao and Sheba. According to a study2 by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), the ride-sharing business is estimated at $60 million, with 6 million rides per month. The ride-sharing market in the capital city of Dhaka has an estimated size of around BDT 22 billion per year.

The COVID-19 pandemic left a large part of the workforce without jobs. Due to the financial precarity experienced by workers, many moved to online platforms to find opportunities for work. Consequently, the number of gig workers in Bangladesh grew rapidly while the platform economy expanded by 27%. In 2021, Bangladesh’s gig workforce grew to around 300,000 location-based workers, while around 500,000 cloud (online remote) workers have made the country the second-largest online outsourcing destination3. As reported by the Bangladesh Employers Federation (BEF), digital platform companies recruited around 30,000 new workers during the pandemic in response to the increased demand for online services.

The gig market, in Bangladesh and globally, is diversifying, with some platforms converting to “super apps,” and some offering new categories of services. Today, platforms are wooing customers with a wide range of services. There are home-based services, such as beauty care, domestic help, baby care, cleaning and repair and pest control; and mobility services, which include ride booking, food & grocery delivery, courier, truck rental and shifting.

Platform companies have benefitted from the country’s rapid growth in internet connectivity and supporting infrastructures, as the government steers forth with a strong agenda focused on building a ‘Smart Bangladesh 2041.’ This flagship initiative aims to transform the country into a technologically advanced state. Digital entrepreneurs are further boosted by the country’s extremely successful mobile financial services, which has found a large and unprecedented user base due to the high density of mobile phone use. Platforms can manage payment between both workers and customers through mobile phones, alleviating the logistical burdens of cash-based transactions.

However, workers on these platforms have had to deal with low wages, poor conditions, and a lack of social security and occupational safety. The Fairwork Bangladesh Ratings 2022 report highlights many of the concerns around pay, working conditions, work contracts, management, and worker representation which are widespread amongst platform workers. The majority of platform workers in Bangladesh’s informal economy do not have access to a financial safety net since most platforms do not provide sick leave, insurance, or coverage for loss of income. Platforms are often opaque regarding contract terms, and worker termination is sometimes done through an automated system without any consultation or opportunity for recourse. As Fairwork, in partnership with the Bangladesh team at DataSense at iSocial, assesses working conditions for a third consecutive year, it is crucial to take stock and evaluate how workers in the platform economy are being treated. The Fairwork Bangladesh Ratings 2023 report will be published in July this year.

As it stands today, Bangladesh lacks any regulatory framework for the labour standards of platform work. Contracts with workers are unilaterally determined by platforms, with exclusivity clauses around wage and safety, deactivation of accounts, dispute resolution and data usage. Task assignments, time to respond, time to complete, rate of pay, and delivery route can all be automatically assigned through the platforms’ use of algorithmic software, on which workers have no option to negotiate. Platforms tend to be asset-light with little investment in staff or infrastructure like physical storefronts. However, this means workers are required to bring in their own equipment and shoulder the cost of maintenance. Platforms also charge considerable commissions from workers, an unregulated and unpredictable practice. As Bangladesh has no nation-wide minimum wage policies, platforms have no legal obligation to ensure a wage floor.

The misclassification of platform workers as “independent workers” is a primary reason for the lack of their fair treatment. Various platforms, such as Foodpanda, Uber, Sheba, and HelloTask, use various terms, including ‘partner,’ ‘individual freelance rider,’ ‘independent service provider,’ etc., that give impressions that they are self-employed, and that platforms have no obligation towards them as an employer. They are, more often than not, labeled as parties running their own business who enjoy flexibility and freedom to work on their own terms.

The immediate questions that arise in this context concern who determines their terms of work, who draws unilateral contracts with workers that set their wage and working conditions. If workers are not an equal bargaining party, how can they be independent partners?

If workers are not an equal bargaining party, how can they be independent partners?

These issues point to the urgent need of a policy framework which provides protections for platform workers in Bangladesh. There is an absence of political will and mainstream awareness along with inadequate efforts for advocacy towards developing a regulatory frame today.

A robust policy framework would mandate necessary protections for workers, a clear definition of what constitutes platform work, and the formation of a regulatory body with associated institutional structure. It is in interest of all stakeholders to work towards a sustainable and fair ecosystem that would ensure the continuous growth of the platform economy in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh has ratified 33 ILO Conventions, including seven fundamental conventions, as laid out in the ILO Declaration to comply with international labour standards. The Labour Act, formulated in 2006, was amended in 2013 and in 2018 to include better access to freedom of association (forming trade unions, etc.), occupational health, safety conditions, and to address harassment experience by women workers. This is further backed by the National Labour Policy 2012 and Labour Act implementation Rules 2015. The Minimum Wages Board has set minimum wages for 44 different types of work, including garment workers; however, platform workers are not in the purview of these legal provisions, leaving them in a desperate situation without legal protection.

Women workers in Bangladesh are increasingly participating in the platform economy, with the majority of them employed in domestic work, beauty, and childcare services. The amended Labour Law of 2013 recognised domestic work as a profession; though, domestic workers would not have access to certain facilities and benefits that workers in the formal sector are entitled to. The Domestic Worker Protection and Welfare Policy was put in place in 2015, which acknowledged that domestic workers are primarily women, who face violence and discrimination, and thus require protection. However, this policy has not made much progress in terms of its implementation. Women platform workers are neither covered by their contract with the platform nor the law against any risks or abuse at work.

HelloTask, one of the early movers in Bangladesh’s home-grown platform space, offers domestic work services for their well-to-do urban customers. Their onboarding training manual for women domestic workers absolves the platform, with complete apathy, from all responsibilities of ensuring the safety of women workers:

“If you face any problem at the home of the service taker, i.e., customer, then if the problem is created by the customer, the responsibility is his/hers. If you create the problem, it is your sole responsibility. HelloTask will not bear any responsibility in this regard.”

Bangladesh has implemented a strong legal framework for overseas labour migration. There are laws and policies in place to protect Bangladeshi labour migrants abroad who work primarily in the informal sector. The Overseas Employment and Migrants Act 2013, Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment Policy 2016, and other associated legal instruments aim to establish a safe and fair system of migration. One primary objective is to ensure the rights and welfare of migrant workers and their families. A strong legal frame has led to establishing the necessary institutional structure that regulates private recruitment agencies and implements legal provisions on the ground. The government needs to take steps to develop a similar framework for platform workers that sets a system of fair pay, decent work conditions, and the protection of workers’ rights.

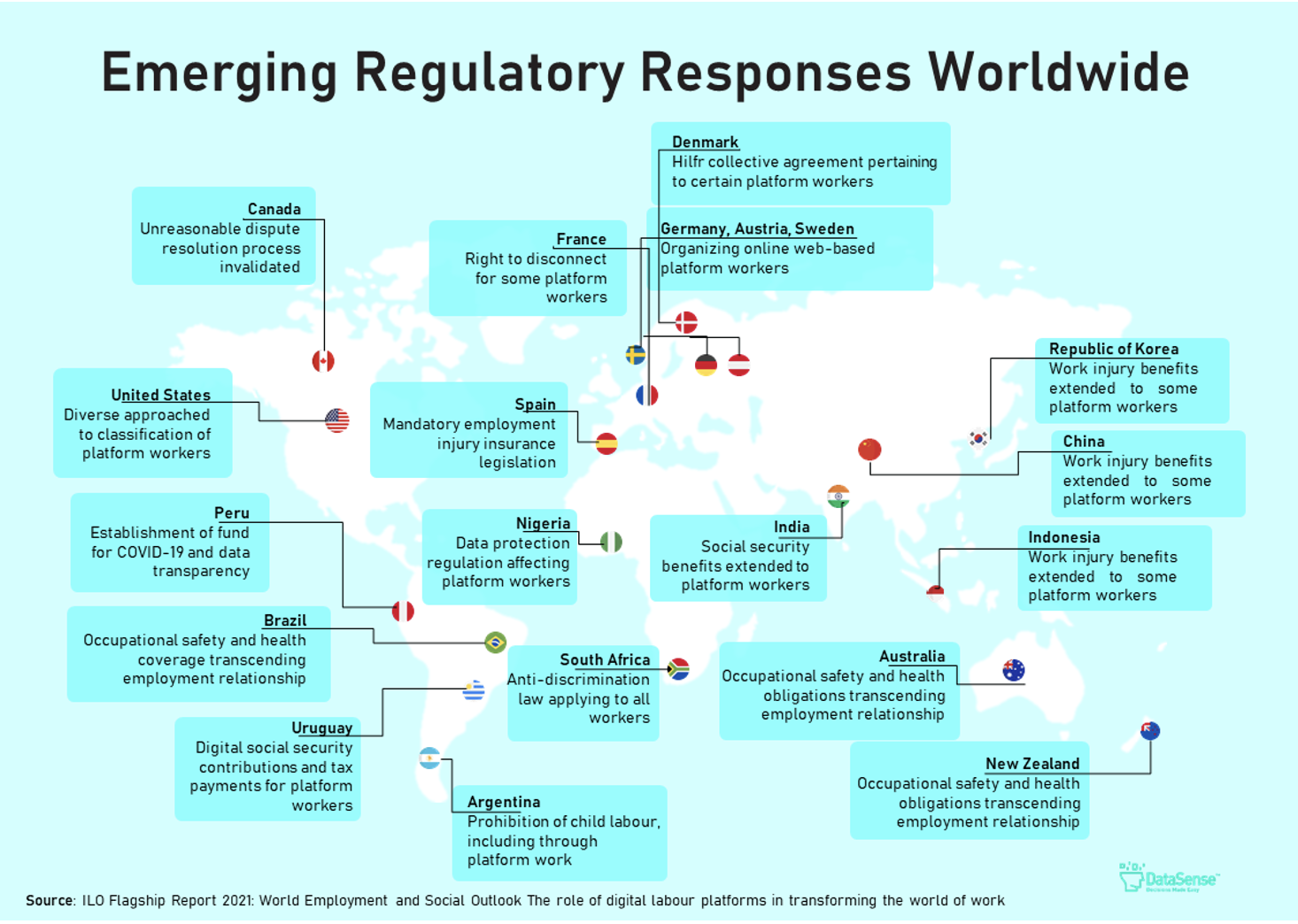

(Source: ILO Flagship Report 2021)

As the platform economy grows globally, dialogues are being held between platform companies, governments, workers and their representatives to ensure that platforms become a powerful driver for fair competition and decent work for all. Powerful discourse, judicial action and workers’ voices are instrumental to developing the policy space of the global platform economy. Solutions, in the form of new policies, regulations and labour law amendments, are evolving around the world. New employment standards are defining the relationship between platforms and workers.

A regulatory framework for the platform economy is essential for Bangladesh that would ensure workers’ basic rights, gender rights including fair pay, decent work condition, social protection, and other benefits. It must ensure non-discrimination, fair termination, bilateral dispute resolution and fair representation for platform workers.

The reclassification of platform workers from self-employed or independent contractors to employees/workers is necessary to formalise platform work. The existing Labour Act must recognise platform workers as ‘employees,’ which would mandate platforms to draw clear and bilateral contracts and provide all standard employee benefits. The inclusion of platform workers in the Labour Act, Rules and Policies will allow workers to form unions that have the necessary bargaining power to achieve their rights.

Researchers, activists, development partners, and civil society actors can play the role of advocates to define new employment standards, new regulations, and amendments to existing labour laws for platform workers.