Fairwork Bangladesh Ratings 2021: Labour Standards in the Gig Economy

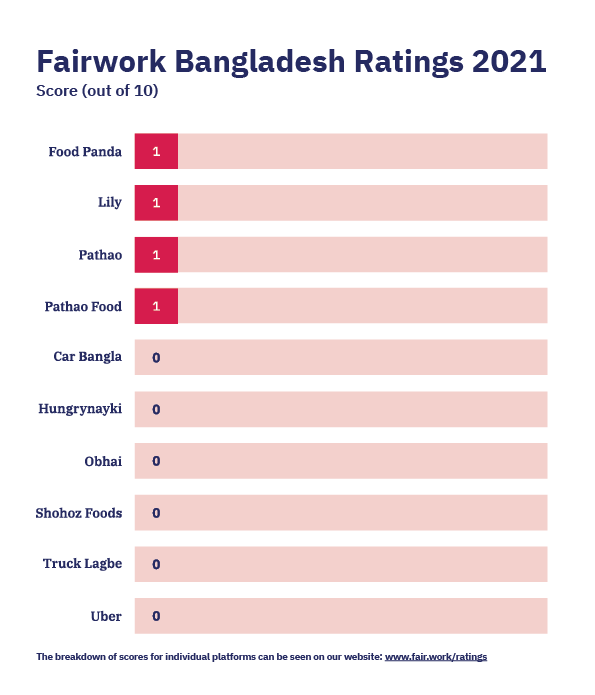

This report presents the first set of Fairwork Ratings for Bangladesh. The working conditions of 10 platforms were assessed and scored (out of 10) using the five Fairwork principles. The scores range from 0 to 1, demonstrating the homogeneously poor conditions faced by gig workers in Bangladesh.

Since the arrival of the first platform company, Uber in 2016, the gig economy in Bangladesh has grown rapidly. The major industries are ridesharing, transportation, delivery and domestic work. The gig economy involves roughly 500,000 active workers, 300,000 of whom are engaged in location-based gig work. The ridesharing industry, currently worth USD 259 million, is expected to reach a market valuation of USD 1 billion in 5 to seven years.

Much like in many other countries, workers in Bangladesh’s gig economy are often classified as independent contractors, as opposed to employees. Companies are thus able to deny workers the benefits of formal employment, such as sick leave, casual leave, annual leave and so on. Moreover, platforms in Bangladesh are not legally required to pay gig workers a minimum wage in consequence of their status as contractors.

The Fairwork project has set out to assess labour practices in the Bangladesh platform economy. Fairwork is an international research project that evaluates working conditions on digital platforms; it is currently doing this in 26 countries across 5 continents, including other Southern Asia countries like India and Pakistan.

Ratings

The Fairwork Bangladesh 2021 ratings evaluate the working conditions in 10 digital labour platforms (Food Panda, Lily, Pathao, Pathao Food, Car Bangla, Hungrynayki, Obhai, Shohoz Foods, Truck Lagbe and Uber) against five global principles of fair work – fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management, and fair representation. We gave each platform a fairness rating out of 10, with points awarded only if there is clear evidence that the principle is being met.

Food Panda, Lily, Pathao and Pathao Food scored 1 point each; Car Bangla, Hungrynayki, Obhai, Shohoz Foods, Truck Lagbe and Uber all scored no points.

Key findings

Fair Pay: Only one platform, Lily, provided documentary proof that workers are guaranteed a minimum monthly wage of BDT 8100. However, despite Lily’s actions to ensure minimum wage was met, it fell short of the living wage threshold in Dhaka.

There are also incidents of net income deficit—16 out of 103 ridesharing workers interviewed were working for a loss due to work-related costs, high platform fees, and the cut taken by intermediaries. These workers continue to work for various platforms to generate everyday cash flow, making the debt trap deeper.

Fair Conditions: Two platforms (Pathao and Pathao Food) could provide evidence of policies to ensure workers’ safety. There have been several significant – though ad-hoc – efforts by almost all platforms to protect workers during the pandemic, yet the efficacy of these efforts are contested by workers’ testimonies.

92 out of 103 gig workers interviewed feared for their safety and security while on the job. Four platforms (Truck Lagbe, Foodpanda, Pathao, Lily) said they were developing an insurance policy for their workers, though only two could provide evidence of ongoing efforts in practice.

Fair Contracts: Performance by platforms in Bangladesh varies when it comes to evidencing clear and accessible terms and conditions in the local context. Only one platform, Foodpanda, received a point for this principle.

In Bangladesh, intermediation is rife in the gig economy, with many workers contracted to non-driving partners or fleet partners. These partners loan or rent their cars to workers by entering into a private and informal ‘arrangement’ with workers and sharing in their earnings. These types of arrangements allow platforms to defuse their responsibility towards workers on the platform.

Fair Management: No platform received any point on Fair Management. Workers from most platforms mentioned they were not supported when seeking redress for arbitrary penalisation and deactivation. In several cases, workers said that the platform used an automated system to inform them of their deactivation, and there was no human consultation or explanation.

Noticeably, two platforms (Pathao and Lily) actively pursue inclusivity and diversity, recruiting transgender communities and women as gig workers.

Fair Representation: We found that workers in four platforms (Uber, Pathao, Obhai, CarBangla) have been active in Dhaka Ridesharing Drivers Union (DRDU). However, platforms have not recognised or entered into collective bargaining with this body. Platforms’ legal obligation to recognize and engage with unions is unclear and contested. Some workers interviewed felt platforms punished them for their participation in union activities.

A more accessible version of the report is also available.

The Fairwork Pledge

As part of Fairwork’s commitment to making platforms accountable for their labour practices, we are launching the Fairwork Pledge. The pledge aims to encourage other organisations to support best labour practices, guided by the five principles of fair work.

Organisations like universities, schools, businesses, and charities that make use of platform labour can make a difference by supporting the best labour practices, guided by our five principles of fair work. Organisations have the option to sign up to the Pledge as an official Fairwork Supporter or an official Fairwork Partner. Those signing up to be a Supporter must demonstrate their support for fairer platform work publicly and provide their staff with appropriate resources to make informed decisions in their supply chains. Becoming a Fairwork Partner entails making a public commitment to implement changes in their own internal practices, such as committing to using better-rated platforms when there is a choice.