Just out! First Round of Fairwork Brasil Ratings: Labour Standards in the Platform Economy

The Fairwork Brasil 2021 report presents the first round of Fairwork ratings for the Brasilian platform economy. The report evaluates the working conditions of six digital labour platforms in the ride-hailing and courier-delivery sectors. The platform scores range from 0 to 2 out of 10. Relatively low scores reveal that there are significant gaps in labour standards across the board and there is still much to be done to ensure fairness for gig workers in Brasil.

Platform work is one of the central themes on the agenda for Brasil’s present and future.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the Brasilian population’s growing dependence on digital platforms to carry out work activities. The number of workers in the delivery sector grew by 979.8% between 2016 and 2021 in Brazil, according to data from the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA). Over the past two years, delivery and transport sectors have been in the spotlight, with platform workers being considered essential. Platformisation has also expanded to various work sectors – with digital platforms offering access to general services and domestic work, in addition to other cloudwork platforms.

Unfortunately, digital platforms are emerging in Brasil in the context of a labour market characterised by deep inequalities, high precarity and the permanent non-universalisation of fair work. One of the big questions is to what extent digital labour platforms have contributed to aggravating this scenario. Platforms exercise a significant degree of control over work processes, through mechanisms such as algorithmic management and datafication, and promote the informalisation of formal activities (such as passenger transportation), expanding informal work. In turn, workers are increasingly dependent on platforms in order to survive economically. Therefore, digital labour platforms have to be analysed in the context of Brasil’s high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

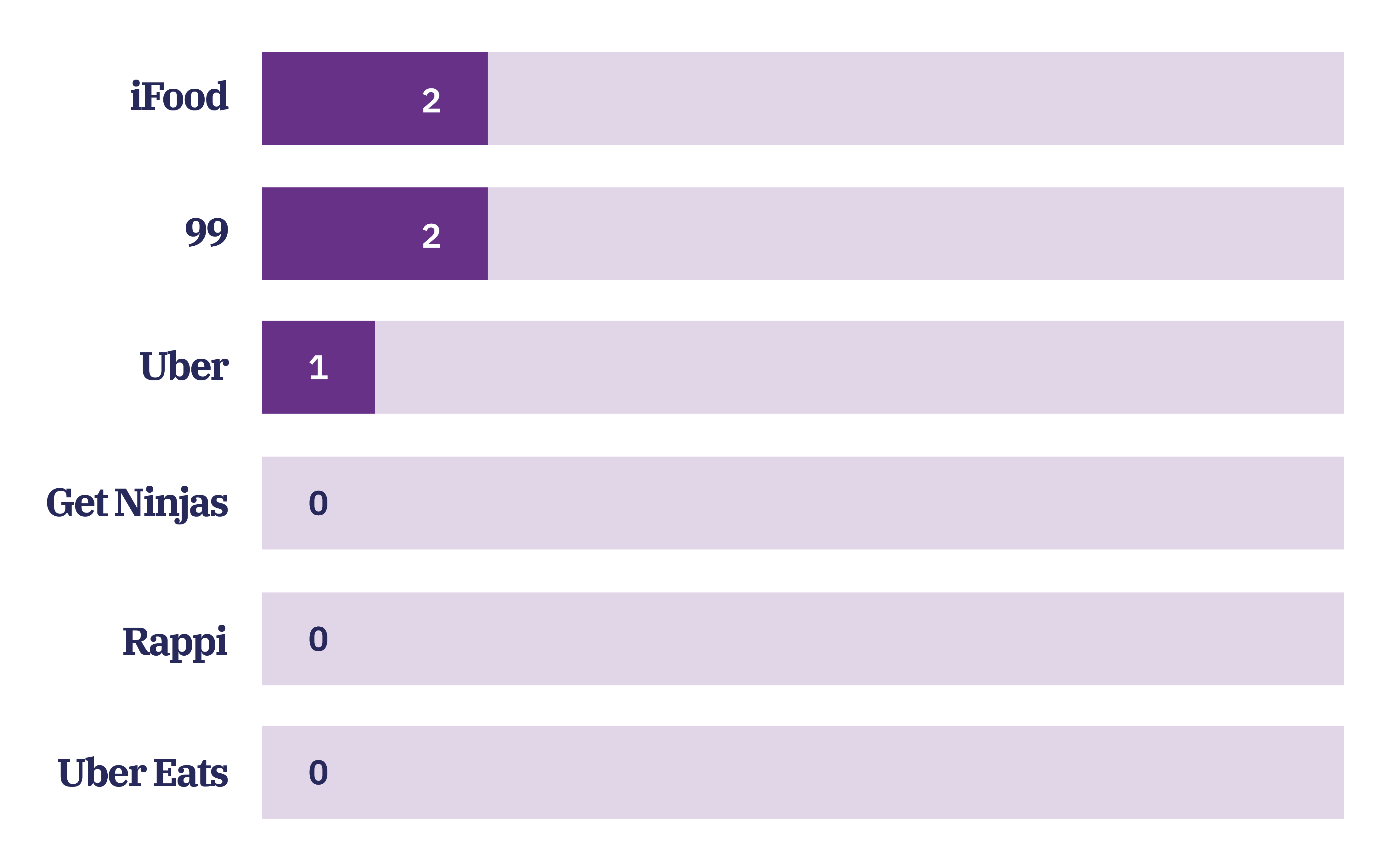

The scores in this first report provide an independent and reliable picture of six digital labour platforms in Brasil and their practices in relation to fair work. The platform scores show that, at the very least, digital labour platforms have been contributing to the maintenance, and, probably, to the aggravation of the unequal and precarious conditions of the Brazilian labour market. In this year, in line with what has been happening in other Latin American countries, no platform scored more than two out of a maximum of ten points. This context is different even from other countries in the Global South – such as Asia and Africa – whose reports have pointed to platforms with higher scores.

Ratings

Fairwork scores digital labour platforms based on five global principles of ‘fair work’ – Fair Pay, Fair Conditions, Fair Contracts, Fair Management, and Fair Representation. Evidence on whether platforms comply with these five principles was collected through desk research, interviews with workers, and platform-provided evidence. The evidence was then used to assign a Fairwork score out of ten to each platform.

The Fairwork Brasil 2021 ratings evaluate the working conditions in 6 digital labour platforms: GetNinjas, iFood, Rappi, Uber, UberEats and 99. iFood and 99 lead the table with 2 points, followed by Uber at 1, and GetNinjas, Rappi, and Uber Eats not receiving any points. Overall, all of the six platforms failed to secure basic labour standards for their workers.

Key findings

- Fair Pay: Only one of the platforms (99) was able to demonstrate that all its workers earn above the local minimum wage, which in 2021 was R$5.50 per hour/ R$1.212,00 per month (2021). Most platforms, however, fail to meet this basic threshold as they do not have a wage floor, and/or charge high commissions or platform fees. Pay rates and working hours are also highly volatile, leading to a high income insecurity for workers. No platform was able to prove that workers earn above the local living wage, calculated by DIEESE as R$24.16 per hour/R$5,315.74 per month.

- Fair Conditions: Two platforms (Uber and 99) were able to evidence actions to protect workers from task-specific risks in line with Fairwork principles. Good practices by these platforms involved effective provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) and clear accident and health insurance policies. On other platforms, if PPE was offered at all, many workers faced significant barriers to access it (e.g. distant pick up locations). Another recurring complaint of workers was the lack of basic infrastructure such as access to bathrooms, rest areas, and drinking water. In addition, many workers face serious health risks from traffic accidents, assaults, excessive exposure to the sun, back problems, stress, and mental suffering. More needs to be done by platforms to mitigate these risks. One platform is however providing workers opportunities for training and professional development.

- Fair Contracts: Only one platform (iFood) was able to provide evidence of basic standards in relation to fair contracts. As a result of their involvement with Fairwork, iFood created accessible terms and conditions for workers with illustrations. However, most platforms still do not provide a contract that is communicated in clear, comprehensible language, and accessible to workers at all times, and they do not notify workers of proposed changes within a reasonable timeframe. No platform was able to evidence that their contracts were free of unfair terms and that they do not unreasonably exclude liability on the part of the platform.

- Fair Management: This principle remains a big challenge in the Brazilian gig economy. No platform was able to evidence effective communication channels, transparent appeal processes and anti-discrimination policies. In this context, arbitrary deactivation and lack of effective communication channels with the platform are the most pressing concerns for workers. Platforms need to introduce clear deactivation policies and processes through which workers can learn about the reasons for their deactivation. Moreover, workers need to be able to talk to a human representative and to appeal to decisions in a transparent way.

- Fair Representation: Only one platform (iFood) was able to highlight significant policies to ensure the voice of workers. Following their involvement with Fairwork, iFood created a Riders’ Forum as a communication channel with organisers and riders in general. However, most platforms do not have a documented policy that recognizes the voice of the worker and the workers’ organisation. Moreover, workers’ rights to freedom of association are often constrained. Several workers report that they have already been penalised for participating in strikes. Therefore, we call upon platforms to respect and encourage workers’ rights to organise and to express their wishes collectively.

The Fairwork Pledge

As part of Fairwork’s commitment to making platforms accountable for their labour practices, we have launched the Fairwork Pledge. This pledge aims to encourage other organisations to support decent labour practices in the platform economy, guided by the five principles of fair work.

Organisations like universities, schools, businesses, investors and charities that make use of platform labour can make a difference by supporting platforms that offer better working conditions. Organisations have the option to sign up to the Pledge as an official Fairwork Supporter or an official Fairwork Partner. Those signing up to be a Supporter must demonstrate their support for fairer platform work publicly and provide their staff with appropriate resources to make informed decisions about what platforms to use. Becoming a Fairwork Partner entails making a public commitment to implement changes in their own internal practices, such as committing to using better-rated platforms when there is a choice.