Platform work in Bosnia and Herzegovina: solution for unemployment or deepening precarity

By Nermin Oruč, Amela Kurta and Ilma Kurtović (Fairwork team for BiH)

The conditions and experiences of platform workers in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) are deeply impacted by the existing precarity on the overall labour market and its institutions such as employment protection legislation, minimum wages, and unionisation of workers. In BiH, platform workers, are frequently categorised as independent contractors, do not have access to the same institutions and safeguards of the labour market as regular employees, which further exacerbates their precarity. This meant they are not eligible for benefits like sick pay or holiday pay, and they might not have a guarantee of minimum income. Platform workers are also exposed to unforeseen shifts in the demand for or supply of services, which may also have an effect on their earnings and overall financial security. To better understand the challenges faced by platform workers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the remainder of the text briefly describes the BiH labour market and its main institutions.

The labour market in Bosnia and Herzegovina is characterized by a high unemployment rate (15.4% in 2022) and a high share of informal employment (30%) compared with EU-27 averages. Available data shows that the highest rate of informality is among low-educated workers. Around 86% of workers with no education and 62% of those with only primary education work informally (Oruč, & Bartlett, 2018). These two characteristics are interrelated: due to the high unemployment rate, job seekers have a weak bargaining position, and are therefore forced to accept unfavourable informal or semi-informal arrangements. In addition, even in sectors where employees have better negotiation position, the semi-informal arrangement with an employer (i.e., envelope wages*) is often voluntary as a way to increase disposable income. Evidence suggests that the average rate of income underreporting in BiH is 6.7%, with a larger presence among the male and younger population (Kurta et al., 2022). This employment trend became even more relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic further exposed informal workers to risk, especially in those sectors where the closures have resulted in job closures and the greatest reduction in income (ILO, 2020). The pandemic crisis only deepened the existing risks faced by these workers, particularly in the absence of a mechanism to reduce the consequences of falling incomes and rising unemployment.

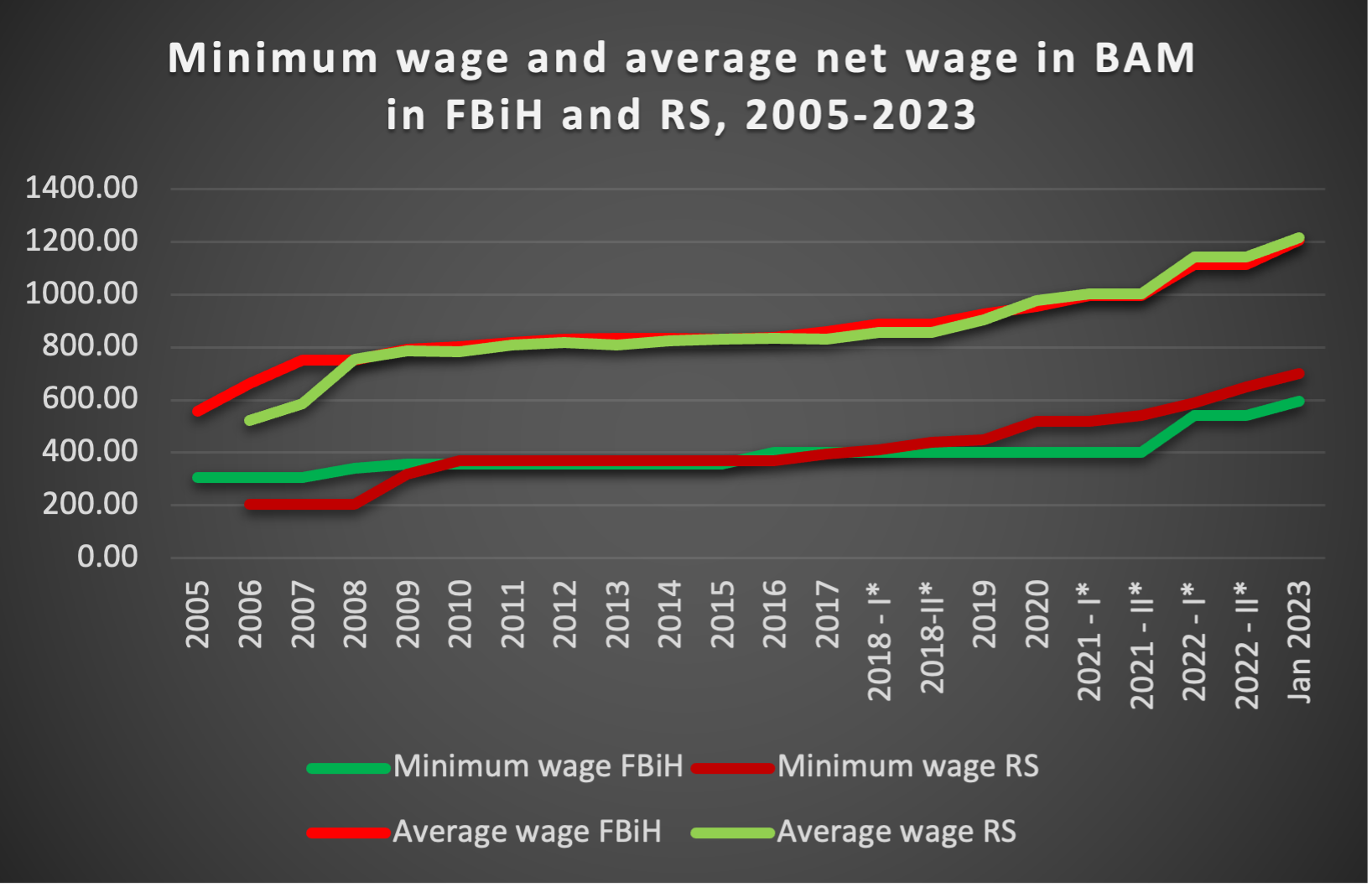

In the range of labour market institutions, the economy in BiH is characterised by substantial enforcement of minimum wage policy. The minimum wage is part of the tax-benefit system in both administrative units (entities) of BiH. In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), it was introduced in 2005 through the General Collective Agreement at a level of around 50% of the average salary. The Republic of Srpska (RS) introduced a minimum wage in 2006 at a lower level than in the FBiH, at around 40% of the average salary. There were several changes in the level of the minimum wage in FBiH (in 2016 and in 2022 and 2023), while in RS changes were recorded in every year and in some cases even during the year, with the last change introduced at the beginning of 2023. As shown on the chart below, increases in the minimum wage seem to follow the increase in the monthly average net wage. In FBiH the share of the minimum wage in the average wage is still around 50%, while in RS it reached the level of 58% (January 2023).

Source: Own calculations based on data from the Federal Institute for Statistics and the Institute for Statistics of the RS for the average wage and government official decisions for the level of the minimum wage; Note: *Changes in the level of the minimum wage in RS during the year

Previous research suggests that increasing the minimum wage in BiH has a significant positive effect on poverty reduction but a limited effect on income inequality (Kurta and Oruč, 2020)**. Therefore, policymakers should consider the effects of increasing the minimum wage level on the entire tax and benefit system and base their decisions on the available evidence. The position of workers to negotiate better working conditions is further aggravated by the unfunctional social dialogue. The FBiH Employers’ Association unilaterally terminated the FBiH General Collective Agreement in March 2018 (Decision on Termination of the General Collective Agreement for the territory of the FBiH, art. 1) and although the social dialogue continued in 2020 there is still no consensus on the new general collective agreement. In RS, tripartite dialogue has continued on a regular basis and yielded some concrete policy-relevant progress and outputs, such as improvements in the field of occupational safety and health.

Student employment is also present, but mainly through informal or semi-formal arrangements due to the lack of regulation on the possibilities for regular students to work during their studies. Some improvements were made in Canton Sarajevo in the Law on Higher Education (Official Gazette of Sarajevo Canton, No. 36/2022) and initiatives at the entity level, as a result of CREDI’s research on Policy Impact Analysis of Changes in Labour Legislation in Bosnia and Herzegovina—Estimating Effects on Public Revenues and Job Creation. There is still a policy gap that needs to be addressed to ensure legal forms of student employment, who are oftentimes working for platforms.

In general, employment protection legislation in BiH is moderately flexible according to the EPL index, which was 2.45 in 2015 (as calculated within the abovementioned CREDI research project on ex-ante assessment of changes in labour legislation in BiH) and 2.60 as reported by the OECD, whereas higher values of the index represent stricter regulation. The index in BiH is still a little higher than the average index of EU and OECD countries, implying that there is room for improvement in terms of higher flexibility and greater employment protection. On the other side, according to the Labour Rights Index, BiH scored 88 out of a possible 100 points and was marked as an economy approaching decent work.

Although regulations provide possibilities for trade unions to play an active role in shaping employees’ status in the labour market, unionisation is still weak. The country has two major union confederations – the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Bosnia and Herzegovina (SSSBiH) and the Confederation of Trade Unions of Republika Srpska (SSRS). The latest research under the Labour Rights Index calculations from 2022 reports that the trade union density rate is 30% and the collective bargaining coverage rate is 50%. The unionisation rate is much higher in the public sector and state-owned companies than in the private sector. In the private sector, unions are mainly organised within one specific industrial sector or subsector. The presence of informal work, including those working on platforms, further complicates the work of unions, given that members can only be formally employed workers.

Access to labour rights arising from existing labour market institutions, and the degree to which they are exercised, vary largely by the type of contract. Various types of (non)contractual relationships exist between employers and employees. The following types of employment relationships can be observed: a) ‘Standard’ open-ended, full-time contracts; b) Part-time work (including involuntary part-time work); c) Self-employment (including platform workers and freelancers, even though that labour legislation in BiH does not recognize this type of business); d) Temporary work (including fixed-term contracts, seasonal and casual work); e) Informal or undeclared work; f) Internship and student employment (including volunteering). When there is a contractual relationship with the employer, platform workers often conclude service contracts, or they are considered self-employed, which means that they bear the costs of social security and employment protection.

Given the situation with the existing labour market institutions and how they regulate employment conditions in the country, platform work brings about various challenges, including the fact that it is still not recognised as a specific employment relationship within the legislative regulation in the country. In the context where high unemployment is pushing workers into the informal sector, combined with an unfunctional social dialogue and moderate employment protection for those formally employed, platform work is considered a possible way out for those who do not have other possibilities, such as students, low-educated persons, and those in long-term unemployment.

Choosing between “two evils”, unemployed people look for a source of income through informal work on platforms, which ensures finding work but does not solve the problem of insecurity. Access to basic labour rights is impossible in the situation of informal employment, which often puts them at risk of job and income loss, injuries at work without insurance coverage, overtime work, and several other situations that can lead to greater insecurity compared to their unemployment status. Even in situations where platform workers become formal employees, due to the practice of income underreporting or concluding a service contract instead of an employment contract, certain social benefits (such as pensions) are reduced or workers do not exercise their rights to, e.g., health insurance or unemployment insurance.

Data on the extent to which these practices are present on platforms in BiH is not known; however, it can be assumed that they exist, considering the general characteristics of platform work and the characteristics of labour market in BiH. Fairwork research in Bosnia and Herzegovina will for the first time offer evidence about the problems faced by workers on platforms, with the aim of providing a basis for discussions of possible changes in regulations. Even before the results of this research are available, solving the problem of platform work begins with the recognition of this specific type of employment by decision-makers, as well as raising awareness of the need to organize workers so that they can fight for their rights.

*Envelope payments work in a way that employers pay the employee officially a lower salary than the average for a similar job, while the rest pay in cash. Only the part of the salary which is officially declared serves as a basis for paying social security contributions.

**Kurta, A. & Oruc, N. (2020). The effect of increasing the minimum wage on poverty and inequality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Economic Annals. 65. 121-137. 10.2298/EKA2026121K.