Platform Workers Still Require Regulatory Protection

There are an estimated 4.4 million platform workers in the UK (Fairwork, 2022). In part because of the lack of specific legal protections for those workers, many of them are often exposed to a wide array of risks and harms. This includes low and insecure pay, a lack of health and safety protections, limited social protection, algorithmic control and surveillance, improper use of personal data, discrimination and the prevention of access to collective bargaining rights.

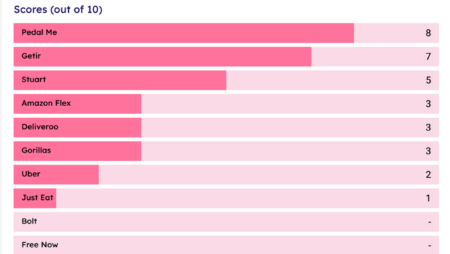

The University of Oxford-based Fairwork project has been studying platform work in the UK since 2020. The project scores platforms out of 10 based on how ‘fair’ the working conditions on the platform are.

As can be seen from the table, our research shows that a majority of platforms cannot evidence even basic minimum standards of fairness. For instance, 10 out of the 12 rated platforms in 2023, could not even guarantee that workers receive earnings at, or above, the UK’s minimum wage, after work-related costs. Furthermore, major challenges for platform workers arise from ‘black box’ algorithmic management systems. Often used by platforms to decipher payment, allocate tasks, monitor behaviour and performance, and discipline or dismiss workers, opaque algorithmic systems are a key driver of stress, instability and vulnerability for platform workers. See the Fairwork 2023 report for more details.

Table 1. Fairwork Scoring for the UK, 2023.

Fairwork scores are ultimately developed not just to hold a mirror up to the sector, but also to encourage platform companies to make improvements to working conditions. The project has, to date, encouraged firms to make 301 changes to policies and practices to receive better scores. These changes include the introduction of strengthened insurance offerings and commitments to the principle of voluntary recognition. However, responsive regulation is required to deliver systemic improvements for platform workers. Without this, platform work will continue to be synonymous with precarious and unfair working conditions.

With the UK general election now upon us, we propose a set of evidence-based recommendations for the incoming Government. These proposals, which are rooted in the findings of our cross-sectoral, multi-stakeholder research, will provide a foundation for fairer and more sustainable platform work in the UK.

Facilitate specific reporting on platform labour by updating statistical reporting in major labour force surveys to account for platform work and requiring platforms to share data about the profile of their workforce. This is necessary for evidence-based policymaking moving forward.

Legislate to close loopholes in employment status by providing universal workers’ rights. This will ensure that all workers are provided with full employment rights, except for those who are genuinely self-employed. To accompany this, in line with the EU Platform Work Directive, switch the presumption so that platforms, not workers, must prove employment status.

Ensure adequate enforcement of employment protection. This could be achieved through the creation of a dedicated body, such as a Workers’ Protection Agency, as well as the implementation of greater penalties for illegal practices and non-compliance. Unions and workers’ organisations should also be empowered to carry out enforcement-related activities, including via the provision of a ‘digital right of access’ (TUC, 2021).

Introduce the right to both sectoral and company collective bargaining, to account for the challenges generated by the monopsonistic and dependent nature of most platform work, regardless of employment status. Following the EU Platform Work Directive, platforms should also be required to establish channels for workers to communicate with each other, without fear of reprisal. Worker atomisation is common in the platform economy, with workers on the same platform often unable to communicate with each other. Ensuring that workers can communicate is fundamental for organising and the identification of collective grievances.

Incentivise shared ownership models and require worker representation on boards. Cooperatively owned platforms have the potential to deliver fairer and more equitable in-work outcomes, but this potential – in the UK at least – has yet to be sufficiently realised. Giving shared ownership a chance would require active support to reduce obstacles, including through economic support, the provision of access to infrastructure, and the reduction of the regulatory burden currently facing prospective cooperators.

Ensure that workers without a physical workplace (ride-hailing, food delivery) have access to toilets and rest facilities. This is a matter of health and safety for all workers. However, it is particularly important for workers who menstruate.

Ensure tip, location and distance transparency. Workers and customers should be informed about how much of the tip is retained by the platform. Workers must also be informed about the delivery and drop-off destination by platforms, to enable them to make informed decisions when accepting a task.

Ensure algorithmic transparency. Workers must be given meaningful tools to understand how algorithmic decisions are made, how they impact they work they do, and how they shape the opportunities they have. To facilitate this, and reduce informational asymmetries, the government should require platforms to provide information about the metrics behind algorithms (including the data collected and the calculations used), in a documented form which is available to workers.

Require that platforms do not subject workers to excessive data collection practices. Workers should be informed about the data that is being collected about them, and platforms should be required to apply the principle of data minimisation (collecting the minimum amount of personal data required to fulfil a legitimate purpose) in their collection processes.

Address common unfair practices in contractual clauses. Contractual clauses that unreasonably exempt the platform from liability for working conditions should be prohibited. Although some of them are not legally enforceable, they still discourage workers from seeking legal redress. Platforms should also be required to notify workers of proposed changes in a reasonable timeframe before they can take effect and prohibited from reversing accrued benefits, or reasonable expectations, on which workers have relied. Where work is location-based, the party contracting with the worker should be identified in the contract and subject to the law of the country in which the worker works.

Require platforms to ensure due process for disciplinary actions including suspension and dismissal. Any disciplinary decision concerning workers should be taken with human oversight. Platforms should be required to institute internal standards, including the provision of a channel for workers to communicate with a human representative (in a reasonable timeframe) and the implementation of a documented process for meaningful appeals of low ratings, payment issues, deactivations, and other disciplinary actions.

Introduce supply chain due diligence. Fairwork has uncovered many examples of platforms outsourcing work to subcontractors. This practice regularly engenders the negation of responsibilities for working conditions. Following the example of Germany, and introducing supply chain due diligence, would require UK-based companies to monitor and report on social and environmental standards in their supply chain, thus creating greater accountability.

These policy proposals offer a substantive path towards the improvement of fairness for platform workers. If the incoming government is serious about improving the lives of working people in the UK and guiding technological development towards the delivery of equitable benefits in the context of the workplace, it should not ignore this body of the working population.

This blog was originally published on the Oxford Internet Institute webpage, here.